Impact Framework

Please Log In for full access to the web site.

Note that this link will take you to an external site (https://shimmer.mit.edu) to authenticate, and then you will be redirected back to this page.

Preamble

The 6.900 Impact Framework is based on the 6.033 Impact Framework developed by Katrina LaCurts, which is in turn based on the Ethical Computing Protocol, created by Abby Everett Jaques and Milo Phillips-Brown.

This framework might appear overwhelming at first! Don’t worry about getting everything “right” on the first try, or on any try; this framework is simply a tool to help you think through your design decisions. For your March 17 presentation, we’re only focusing on Steps 1.1-1.3. We’ll move on to later steps in later deliverables, once you’ve gotten familiar with the earlier steps.

Introduction

The decisions we make when we design HW/SW systems affect more than just the users and the developers, and moreover, they do not affect all stakeholders equally. This framework contains a series of prompts and other tools to help you work through questions of impact. It is meant to be iterative and collaborative, and can be applied at lots of different points in the design process. For instance, one can assess the impact of the entire system, of a particular design decision, etc. As you work through it, it may bring up questions that you can’t answer yet! That’s okay; the important thing is to keep thinking about these questions.

It’s useful at multiple steps during the design process: at the start, when you make a big design decision, as you begin your evaluation, etc.

Answer the following questions:

- Describe what you will produce with this project, in 2–3 sentences of plain language.

- Explain why it’s worth producing, in 2–3 sentences of plain language.

To help you answer these questions, think about the following:

- Who is your project for? Who isn’t it for? Why should each group care?

- What is the problem you’re trying to solve? Are there existing solutions? If so, what’s different about yours?

What’s the best-case scenario for your project? What’s the worst-case scenario?

You should have several answers to those questions. One best-case scenario might have to do with how your project is received by users or our partner; another might be about how it advances the state of the art. One worst-case scenario might have to do with enabling bad actors; another might be about your career.

To help you think through these scenarios, consider the following questions:

-

Think about novel uses: What kinds of domain-hopping are possible? You have a certain kind of use in mind, for a particular area of life or kind of activity. But what else could your system be used for? What would be different if your system was used in ways you don’t intend?

-

Think about bad actors: How could someone appropriate your system for malicious purposes? What would happen if they did?

-

Think about failure modes: Nothing works perfectly all the time. What can go wrong with your system, and how? What will be the effects when failures occur?

-

Think about differences in benefits and harms to people. Could a member of a group affected by your system -- especially a member of a group that’s been historically disadvantaged -- show you that there’s something about your system that affects them differentially? How?

You’ve already started to think about how different stakeholders are affected by your project; let’s enumerate those stakeholders so we can start thinking about who’s affected.

The different futures you thought about previously will affect different stakeholders differently; the best-case scenario for one stakeholder might not be the best-case scenario for another.

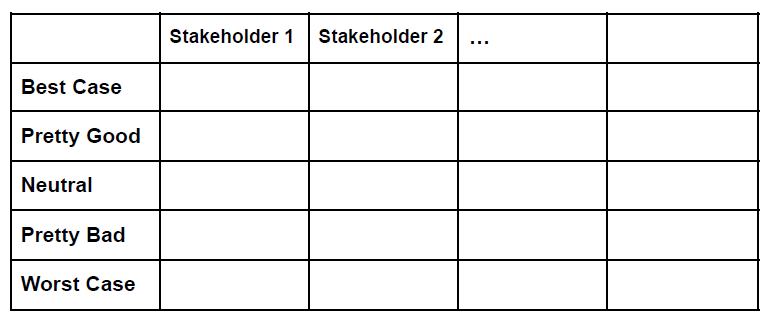

We can capture this idea with a Change Matrix: a table that describes how your project might go well or badly to any degree, for each of your stakeholders.

Generate as many possibilities as you can think of, filling in the cells. It may be helpful to think about different timescales: some short-term downsides generate longer-term upsides, and vice versa. You’ll come back to this Change Matrix in Step 2 of the framework.

To help you think through some of these scenarios:

- What will your family brag about when they talk about your project? What will they avoid mentioning?

- What would make people fight to be put on a team developing this project? What would make them refuse?

- How could your project end up as a feel-good story on the nightly news? How could it end up as the subject of a Pulitzer-Prize-winning exposé?

- If a historian writing a hundred years from now talked about your project, what do you hope they’d say? What would make you hope they didn’t mention your name?

- What would the plot of a Hallmark movie about your project be? What about a Black Mirror episode?

At this stage, you’ve thought about the stakeholders affected by your project, and the impacts of various outcomes on those stakeholders. Step 2 is all about refining this process: being more rigorous in our understanding of what exactly is good and bad about the futures you’ve imagined, and for whom.

The futures you envisioned aren’t just good or bad; they’re good or bad for someone. It’s time to be explicit about who those someones are.

We’ll start by refining our idea of who’s impacted by your system.

- Look back at your Change Matrix. For each possible future (i.e., each cell in the matrix), ask yourself if there are subgroups with a stakeholder group that will be affected differently. If so, add them. For example, users may have quite different experiences depending on factors like age, race, gender, socio-economic or health status, geographic location—or even something like height, or hand size, or familiarity with Star Trek. So ask yourself what it is that makes a future work well or badly for a stakeholder group, and then think about whether subgroups will have different experiences.

To help you think through possible stakeholders and stakeholder subgroups, here are some starting points:

- People living in areas or communities that have/don’t have your system

- People who might be put at risk by your system, if any

- People who might experience secondary effects of your system (e.g., from some sort of disruption of operations

Now that you have a detailed list of stakeholders, it’s time to understand how they are affected. The end-goal of this step is to refine your Change Matrix, noting that you now have a more precise idea of the people/groups affected (thanks to Step 2.1); the Moral Lenses tool below will help you do this.

To this point, we’ve been relying on a loose, intuitive sense of things going well or badly. But it’s time to get clearer about what exactly we mean when we think about the impact of our system on stakeholders.

The Moral Lenses are three ways of looking at a possible future, each of which brings different aspects of that future into view. Using them is a way to understand in what sense a future is good or bad for someone.

Working through each lens in turn is also a way of doing a kind of moral due diligence — making sure we are taking all the morally significant aspects of a project into account.

Lens 1: Outcomes

- What’s different for stakeholders after your system exists, as compared to the starting state?

- What good or bad things do they have more or less of?

Those costs and benefits can come in the form of just about anything: money or time or power or prestige; opportunities, abilities, or liberty; pleasure or pain; cupcakes or cat videos.

Many or even most of the futures you envisioned probably speak the language of outcomes. But this isn’t the only way things can be good or bad.

Lens 2: Process

- Were stakeholders given due care, respect, and consideration in the process of producing the outcome?

This lens is motivated by the thought that sometimes the ends don’t justify the means; there can be good outcomes that we shouldn’t pursue, because what it would take to achieve them would be unacceptable.

If I notice spinach in a colleague’s teeth, I shouldn’t reach over and pick it out myself; if a crying baby is causing passengers on a long-haul flight to become increasingly agitated, I shouldn’t relieve their suffering by tossing the baby out of the plane.

Lens 3: Systems

- How are benefits and burdens—both in Outcomes and in Process — distributed among stakeholders? Is the distribution fair?

This lens draws our attention to the way that it’s not just whether there are net benefits, or whether the process was appropriate; it also matters what the patterns are. If all the benefits flow to one group, while all the burdens are borne by a different group, that can be morally significant, and it certainly requires justification.

So we want to know: are background conditions and historical patterns of marginalization, inequality, and oppression reduced, or reinforced?

The possible futures in your Change Matrix are labeled according to degrees of general goodness or badness; now you will get more precise, saying for whom a future is good or bad, and in what way.

-

For each cell in your Change Matrix, indicate which stakeholder(s) it’s ideal for—and any stakeholder(s) it’s not ideal for. (The cells of your change matrix might get large! Feel free to change the format into whatever works for you; you don’t have to keep it as a table with cells.)

-

Use the Moral Lenses to help you think about ways things can be good and bad for stakeholders that may not be explicit in your initial description of the possible future. Add that information to your cells.

Using the Impact Framework

At this point, you’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how the decisions that you’ve made in your design might impact different stakeholders. You may have made changes in your design in response to this exercise — for example, rejecting a small performance gain that would also have negative impacts on a particular group. In your upcoming presentations, you should use the conclusions you’ve drawn from this framework as part of your justification for your design decisions.